Phare Circus’ “Sokha”: A Journey of Healing Through Art

“Sokha” is a powerful performance by the Phare Circus that tells the story of a young girl haunted by the horrors of the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia. It’s a deeply moving tale of resilience, healing, and the transformative power of art.

More than just a performance, Sokha is inspired by the real-life experiences of the founders of Phare Ponleu Selpak, a school that uses art to educate and heal children affected by war and poverty. Through stunning acrobatics, dance, live painting, and music, the show takes you on a journey through Cambodia’s recent history, from the peaceful pre-war era to the devastation of the Khmer Rouge and the country’s gradual reconstruction.

Sokha’s story is one of personal struggle and ultimate triumph

Unraveling the Cambodian Symbolism in “Sokha”

“Sokha” is more than just a performance; it’s a poignant exploration of Cambodia’s recent history, infused with rich symbolism that adds depth to the narrative. Let’s unravel the captivating Cambodian symbols that make “Sokha” an emotional rollercoaster ride:

Symbolism of Boxes: Building and Rebuilding

Throughout the show, you’ll notice the creative use of boxes. At first, they’re carefully arranged to depict the serene Angkor Wat during Cambodia’s peaceful times. Later, they transform into desks for vibrant students who eventually seek refuge under them in times of terror. As these boxes tumble from great heights, they symbolize the crumbling building blocks of cities. These boxes represent the enduring burdens that people carry due to chaos. In the end, they take on a new shape, signifying independence and the path towards a peaceful and abundant Cambodia.

Live Painting: A Canvas of Emotions

There is deep Cambodian symbolism in the live painting during the performance. The show kicks off with a traditional Buddha statue, evoking memories of a peaceful, religious, and thriving Cambodia. But then, the canvas transforms into a depiction of bombs exploding, portraying the devastation and despair of the Cambodian people during those dark times. The red handprints on the canvas reflect the desperation and sadness of those yearning to escape the Khmer Rouge’s grasp. The destruction of religious freedom is vividly portrayed as the original Buddha is covered in black paint. What’s revealed is a chaotic scene, turned upside down to reveal a skull. It’s a stark reminder that the regime led only to death for millions of people.

Social Evolution through Painting

The final painting tells a vivid story of societal evolution and reconstruction. As Sokha returns to Cambodia after being a refugee, it’s the 80s and early 90s, a time when the country, after the Vietnamese occupation, starts to rebuild. The countryside is depicted as a peaceful and generous place where people can thrive through their hard work. Time marches on as the painter transforms the canvas with roads, lights, and buildings, illustrating the country’s gradual resurgence.

Masks: Unmasking the Past

The use of masks to portray the Khmer Rouge creates haunting and disturbing characters. However, there’s depth beyond the fear factor. The masks symbolize the transformation of ordinary people into monstrous roles during that period. They represent the dual nature of these individuals, showing how they embraced a dark side when they took on their roles. Some even remove their masks, revealing their vulnerability and the inner turmoil they endured. It’s a reminder that even the perpetrators were victims themselves.

“There is one part in the show where an executioner is feeling powerful by executing others. Suddenly, when he’s done, he looks back and he’s scared – he takes off his mask. It’s the symbolism of who you are behind that role you had during the war. The executioners were also victims at the same time.”

There is also a ‘rola bola’ scene in the Khmer Rouge period, which is very symbolic. “It shows how they tried to build a country and society which was very unstable. They are not building on solid foundations and so it was a disaster.

Art Therapy Through Live Performances

One of the most touching moments in the show involves a juggling act. A traumatized young student struggles with black juggling balls, representing his burdens, until Sokha replaces them with vibrant orange ones, symbolizing the power of art to transform negativity into hope.

Sokha’s Return: A Message of Healing Through Art

As Sokha returns to Cambodia as a thriving refugee, the show’s core message comes to light – the healing power of art. Through her teaching, Sokha becomes a beacon of hope, transforming the lives of countless Cambodian children and helping them confront their inner demons.

“Sokha” at the Phare Circus is not just a show; it’s a journey through history, emotions, and the incredible resilience of the human spirit. If your travels take you to Cambodia, seize the opportunity to witness the profound Cambodian symbolism in “Sokha” – an immersive experience that transcends entertainment and leaves a lasting impact on your heart and soul.

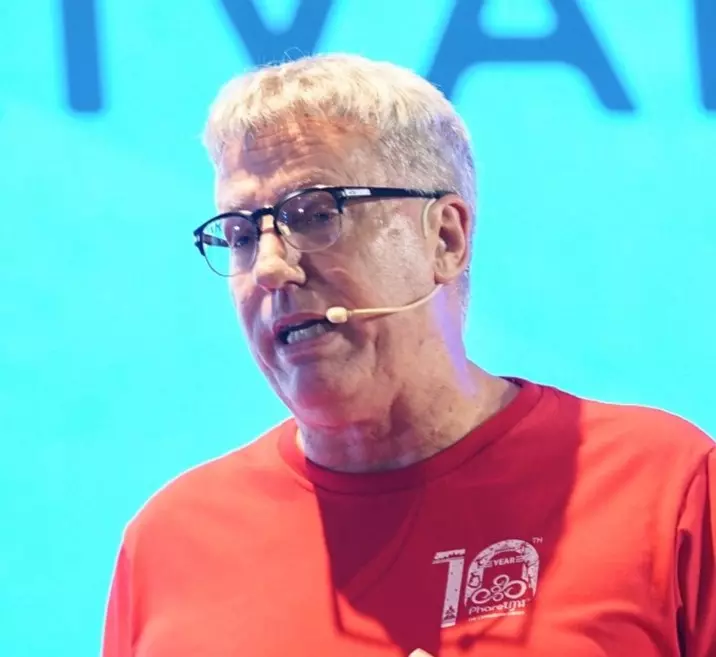

About the Author - Craig Dodge

Craig Dodge is the Director of Sales and Marketing for Phare Performing Social Enterprise, parent company of Phare, The Cambodian Circus and Phare Creative Studio. Craig gets great satisfaction by applying his travel industry experience to Phare's missions of sustaining jobs in the arts and funding artistic and academic education at Phare Ponleu Selpak non-profit school. He is also driven to promote the unique experiences awaiting visitors to Cambodia. When he's not working, you can often find Craig cycling in Angkor park.